Ketamine—Horse Tranquilizer? Party Drug? Or Mental Health Breakthrough?

For those unfamiliar with ketamine’s safe and effective clinical use, fear or misinformation often the default. The truth, as always, is more complex.

Regarding the horse tranquilizer trope: Yes, ketamine, like all pharmaceuticals, was tested in animal first. And yes, like many drugs, it was approved for veterinary use before human use. This is a common way for pharmaceutical companies to recoup some of their research costs while working out the dosing, safety and efficacy in human trials. (To that end, NyQuil in a large enough dose, or any sedative for that matter, could knock down a horse. But you, the client, are not a horse, and we clinicians are not vets.)

Regarding its abuse, ketamine also was used as an anesthetic in the Vietnam War and, like many other drugs on the battlefield, made its way into illicit circles. This was amplified by the publication of several books recounting psychedelic experiences on ketamine in the 1970s, including the musings of Gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson. Because of this misuse, ketamine was placed among the class III substances of the US Controlled Substances Act in 1999, along with anabolic steroids and painkillers like codeine. The classes or schedules basically reflect the potential for abuse. (For comparison, heroin is schedule I, cocaine is schedule II and valium is schedule IV). Ketamine is still frequently abused as a “club drug” which explains the hesitance among those unfamiliar with its safe, controlled use in a clinical setting. This merely emphasizes the need for physician oversight in ketamine administration, (Not via Zoom with a remote guide and a box of lozenges, but at the bedside throughout, controlling the infusion and monitoring the effects). Still, when used appropriately in a clinical setting, the risk of addiction is extremely low. To the contrary, ketamine is potentially beneficial in alcohol use disorder.

However, “horse tranquilizer,” “party drug” and addiction alarm are minor digressions in the story of ketamine. It is a dissociative anesthetic that has been on the World Health Organization list of essential medicines for decades. It was first synthesized in 1962 and first tested in humans two years later. Clinicians have used it in the young and old for half a century because of its wide margin of safety. In the last two decades, an emerging body of evidence has shown its salient effects in several mental health conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and treatment resistant depression (TRD). What follows is a brief review of the recent emergence of ketamine as a potent adjunct in treating mental health disorders, the profusion of ketamine clinics and what to look for in choosing one, as well as the long history of safe medical use of this remarkable drug.

Ketamine for Mental Health Disorders

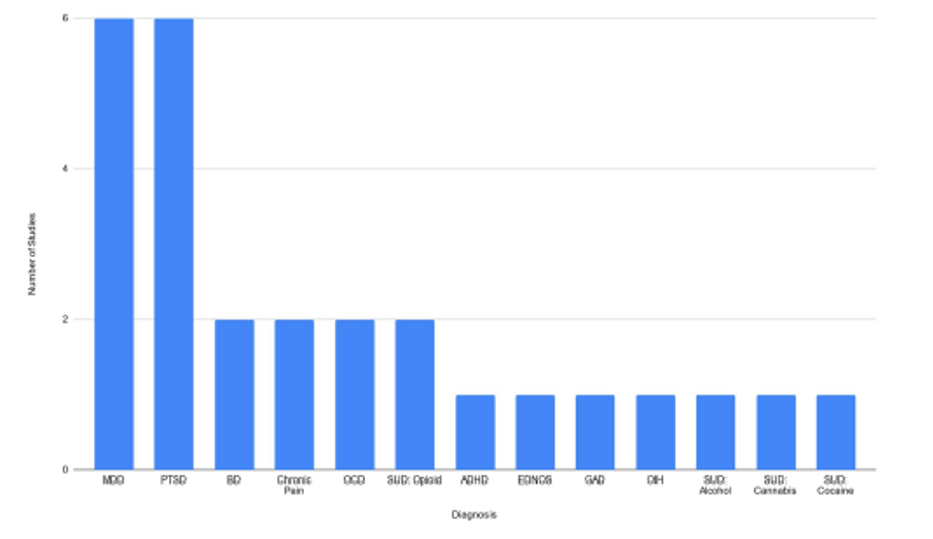

About 20 years ago, the first studies began to appear in the medical literature about ketamine for mental health disorders, and the evidence is building with seven randomized trials, the highest form of evidence, to date (see Figure). This is fairly significant for a drug that has been off patent for decades, meaning there is no financial dog in the fight (the exception being the s-ketamine nasal spray Spravato, which costs as much as $700 per dose). After decades of being limited to SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) and older drugs, the arrival of a new approach to treatment resistant depression and post-traumatic stress disorder was, and is, exciting. This new hope was not tucked away in obscure psychotherapy journals but heralded in the auspicious pages of Science, Nature and the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). Ketamine, a noncompetitive NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptor antagonist, probably works by inducing “neuroplasticity,” though several other mechanisms have been proposed. In layman’s terms, it is like a reset button, perhaps allowing the mind to step back from well-worn depressive thoughts and ruminations and choose another, healthier path. However, the effect is short-lived on its own, a week or so. This certainly has value to the deeply depressed, but short of frequent redosing, (i.e. clinics that insist on selling packages) which carries significant safety risks, it is not a satisfactory long-term solution.

Enter psychotherapy, which has its own wealth of evidence in the same list of mental health conditions. It is a general paradigm in mental health that drugs and talk therapy work separately, but together there is a synergy that is more than the sum of its parts. Rightly so, the term Ketamine-Assisted Psychotherapy (KAP), arose as a promising evidence-based path to symptom relief for millions suffering from depressive symptoms resistant to SSRIs and other traditional therapies.

But what exactly is KAP and how can the discerning consumer know what they are buying into? The answer, as always, is to follow the literature, the evidence, the map of what actually worked. We’ve done that here for you. This graph shows the number of randomized control trials that support KAP organized by various diagnoses.

What is KAP? Defining the intervention

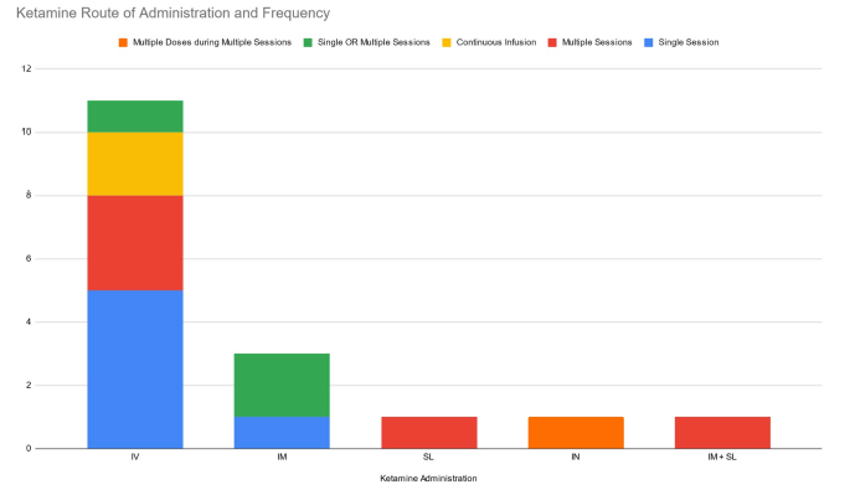

To define KAP, one must break it into the two elements. First, ketamine given at “subanesthetic” doses for mental health conditions generally has meant 0.5 mg/kg given intravenously over 40 minutes. This is about 35 mg in the average adult (roughly the same dose given to a 3-year-old to set a broken bone, though for that it is given all at once, not over 40 minutes). This is where the best randomized evidence lies. There are a few studies of intramuscular, intranasal and sublingual administration, but the evidence is less robust (see Figure).

Practically speaking, intravenous administration is more difficult. It requires expertise in placing an IV and equipment to administer the infusion, but the absorption is more predictable and reliable, as is the effect. Most importantly, it can be turned off immediately. This is no small thing medically if a patient is having an adverse effect such as hypertension, tachycardia, respiratory depression—or a panic attack. This exacting physician control is even more important to the patient having a dysphoric experience (an “emergence reaction” in medical speak or a “bad trip” in drug parlance). The infusion can be stopped, the “bad trip” shut down and even immediately rescued with other intravenous medications such as versed, which not only stops the dysphoria but may erase the memory of it, the so-called retrograde amnesia effect of benzodiazepines. Once an intramuscular, oral or intranasal dose is in, it is in full force until it is metabolized in several hours, assuming normal liver function.

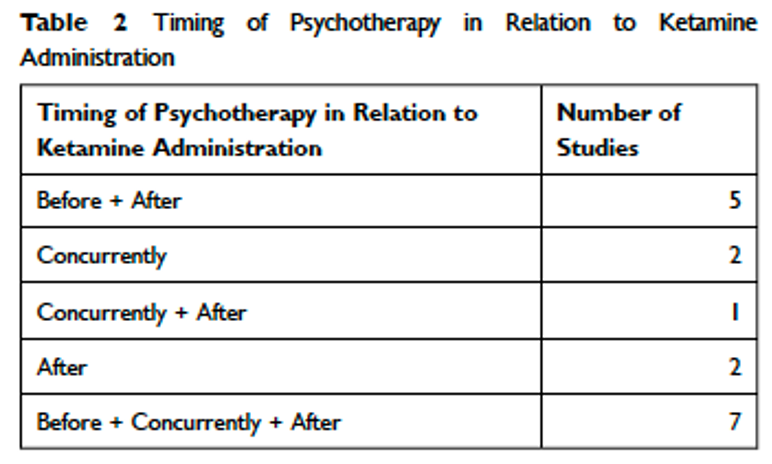

The psychotherapy component of KAP is less well defined, as is the timing. Most studies used Cognitive Behavioral Therapy or mindfulness-based interventions with the number of sessions ranging from 4 to 60 (median was 11). In our case, we often use EMDR to further amplify outcomes. The timing relative to the ketamine infusion was also variable though most studies used before, after and during or only before and after (see Table).

The take-home point of reviewing the published evidence is that a protocol of ketamine administered intravenously at 0.5 mg/kg over 40 minutes along with psychotherapy before and after or before, during and after most closely hews to the highest quality evidence.

The profusion of Ketamine Clinics and home use

When something is shown to work, there is always mission creep, within medicine but even more concerning without. Antibiotics are a great example. They treat bacteria, not viruses, but anyone who is gotten a Z-pack for a head cold will swear by it. It just so happens that by the time someone seeks help for their symptoms they are usually on the tail end of the viral course. They take the pills, and they get better. The pills had nothing to do with it, but it is hard to convince the patient of that. How much worse, then, is unsupervised home use of ketamine? The New York Times has done an excellent job of covering the danger of the Silicon Valley approach to ketamine, all Zoom calls and Fedexed lozenges and not nearly enough medical oversight. It is cheap, but you get what you pay for. (It may not be so cheap if you factor in the cost of side effects of chronic use such as the catheters you may need for your urinary incontinence.)

That is one end of the spectrum, but there are several other business models purveying ketamine that the cautious should be aware of. There are strip mall operations with minimally trained staff giving intramuscular injections and video monitoring with off-site medical direction. They may or may not have a nurse practitioner or physician assistant on site (you should definitely ask!). Some are true medical clinics, which is much better, but few offer commensurate psychotherapy, and very few, if any, have a physician onsite, much less at the bedside. By comparison, nearly all the studies were performed in a university or hospital clinic setting.

This is not meant to scare anyone, but if you give a drug a hundred times you may achieve a false sense of security that nothing bad ever happens. But give it a thousand times and you see the rare complication that nearly kills someone. This is the value of a physician prepared for the 1 in 1,000 complication. If you are among the 999, you may fail to see that value. If you are the unlucky 1, it might save your life. You should ask your ketamine provider about the complication rate and their preparedness for catastrophe, (such as respiratory depression or cardiac arrhythmia or a panic attack), what medical equipment they keep on site and what level of training their personnel have. They should have monitors, oxygen, airway rescue equipment and a defibrillator, and training should include advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) and ideally on-site physician medical direction. If they deflect and tout their virtual reality glasses, turn and walk away.

As for the “P” in KAP, it’s best to have a psychotherapeutic alliance already established. For KAP to get enduring meaningful results, ideally, you and your attending therapist should have a prior session (or more) to explore your history and understand your goals to be further developed during your session and in follow up care. This is a step we hold standard. Mainly, we want you to get the most out of your ketamine session and get out of duress fast. This is why we don’t sell packages. Your experience is individual. Ultimately, you will decide when or if you need additional infusions based on your outcome. (In general, if we do successive ketamine sessions, we give months apart, using the client’s reported symptoms and our observations as guide.) In some ketamine clinics, the therapy piece is often overlooked—but it’s the part that endures. Using this window of neuroplasticity therapeutically is where the rubber finally meets the road. When you are out of the ditch of depression or no longer ruminating, there is a level playing field to do the cognitive work. This is why combining the medically-monitored infusion model with a skilled therapist (not a peer-monitor, journey person or shaman) you feel safe with or who understands your history is ideal. An assigned therapist you do not know well or an attendant dutifully employed to scrawl notes during your infusion is no more effective than using the voice memo app on your phone. Pairing this opportunity of neurogenesis with a therapeutic alliance and evidence-based therapies is like throwing everything but the kitchen sink at the problem—in the best way. For those who have carried the weight of depression or extensive trauma for months or even years, relief can’t come soon enough.

Ketamine, a history

Among the many drugs used for sedation in clinical practice, ketamine by far has the longest safety record. In 1962, organic chemist Calvin Stevens synthesized the short acting compound 2-(O-chloro-phenyl)-2-methyl-amino cyclohexanone, and, because it contained a ketone and an amine, he christened it “ketamine.” The wife of Stevens’ anesthesia colleague coined the phrase “dissociative anesthetic” to describe the disconnected, dream-like state the drug produced. (This was much better than her husband’s term “schizophrenomimetic,” which was not only inaccurate but woefully unappealing.) The effect was later understood to be the electrophysiological dissociation between the thalamocortical (sensory superhighway) and limbic (emotional) systems.

The key difference with ketamine was that it did not have much effect on breathing and airway protection reflexes, unlike other sedatives which often require airway interventions such as endotracheal intubation and ventilatory support. This becomes very important in low resource settings such as the battlefield or a Developing World country. In rich countries, it served as an alternative to powerful opioids which can have a rebound increase in pain when they wear off, not to mention higher addiction potential.

In the 1980s, researchers discovered that activation of the glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate calcium channel (NMDA receptor) was responsible for induction of synaptic plasticity. The discovery of the NMDA receptor and its noncompetitive inhibition by ketamine prompted large advances in the understanding of mental disorders. It became clear that memory and consciousness were the result of synaptic plasticity and fine tuning of glutamatergic influences of NMDA receptor-mediated phenomena.

It is somewhat ironic that decades after ketamine was invented to make patients unconscious, the first randomized trials were published showing its benefit to improve their depressive symptoms in waking life. After two decades of study, it has emerged as a safe, promising evidence-based therapy for the millions suffering from these diseases.

Why not Psychedelics?

Seritonergic psychoactive compounds such as psilocybin (magic mushrooms), lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD or “acid”), peyote, ayahuasca and methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA also “ecstasy” or “molly”) have shown promise in some early trials and bear watching. (As highlighted before, ketamine while often lumped in this group, is a dissociative anesthetic and not a psychedelic.) Practically speaking, psychedelics are also currently illegal in much of the United States. The US FDA is expected to reclassify psilocybin and MDMA in the coming years which may lead to much needed further research on the safety and efficacy of these compounds for treating mental health disorders. In the meantime, without clinical support in place, exercise great caution in the offerings of shamans and trip guides and magical mystery tours. As you probably would not take great comfort in your gastroenterologist promising a “journey” while prepping you for a colonoscopy, similar offerings from other health professionals should give you equal pause.

Ready to begin? You can book a free hour Zoom session here to learn more about our Lake Austin Psychotherapy’s Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy protocol.

References:

Mion, Georges. History of anaesthesia: The ketamine story – past, present and future. European Journal of Anaesthesiology 34(9):p 571-575, September 2017.

Drozdz SJ, Goel A, McGarr MW, Katz J, Ritvo P, Mattina GF, Bhat V, Diep C, Ladha KS. Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy: A Systematic Narrative Review of the Literature. J Pain Res. 2022 Jun 15;15:1691-1706.

Zanos P, Moaddel R, Morris PJ, et al. NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Nature. 2016;533(7604):481–486.

Wilkinson ST, Howard DH, Busch SH. Psychiatric practice patterns and barriers to the adoption of esketamine. JAMA. 2019;322(11):1039.

Li N, Lee B, Liu RJ, et al. mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science. 2010;329(5994):959–964.